Why ageing research?

Record holders for long life

Born before the French Revolution and already older than any human that ever lived when the Titanic sank, the Greenland shark is the world’s oldest known vertebrate. It lives in Arctic waters and can survive for up to 500 years. Even more extreme life spans are known from the plant kingdom. A long-lived bristlecone pine tree named "Methuselah" in California has been found to be almost 5,000 years old and counting. As it first broke through the forest floor as a small sapling, the pyramids of Giza were still being built in Egypt!

Among land mammals, we humans have the longest lifespan. A French woman named Jeanne Calment was the oldest person ever to have lived. She died at the age of 122 years and 164 days in Arles, France.

We need to extend our health span

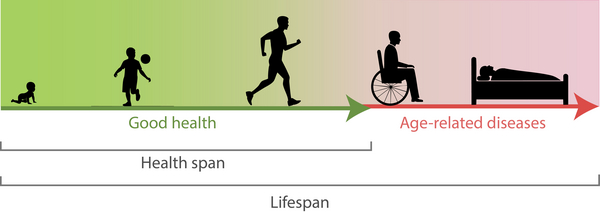

Over the last 150 years or so, our lifespan has more than doubled. Major successes in modern medicine such as better hygiene, vaccines and antibiotics are largely responsible for this. However, we often spend a considerable portion of the latter part of our lives suffering from major health restrictions. This is because our health span, i.e. the amount of time we spend in good health, has not increased in step with our lifespan.

So today we are ill for longer before we die. This is not just a problem for individuals, but also a challenge for society. Among other things, it is associated with immense costs.

Research on the biology of ageing aims to change this: it seeks to understand exactly what happens during ageing, so we can find ways to extend health span.